What is a healthy soil? Across time and cultures, soil health has often been used as a barometer for societal health.

The now predictable argument is that if civilizations do not tend to the health and fertility of their own soil, they

will eventually fall. The geologist David Montgomery’s book, Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations

tracks this argument from Mesopotamia to the present while also providing a history of how scientists have come to

understand the importance of soil as the “skin of the earth”. And yet, the question remains: what is a healthy soil, who

gets to decide such things in any given place and time and what measures of coercion or freedom are taken to cultivate “healthy”

soil? We might look back and in retrospect see what was considered healthy was actually harming. Thus, health is a historically

and culturally constructed judgement of soil that is never without debate. This unit aims to construct a more nuanced conversation

about how human health and soil health have been intertwined at different historical moments. We argue that societies have defined

and intervened in soil health in a variety of ways and that we are now living out the legacies of these various definitions. The

unit starts by considering how we evaluate soil, building on some of the readings and exercises from Unit 1. We then

look at how humans intervene to change soil health, and how soil health changes human health. The final day considers how soil is often seen as a

reflection not just of individual bodies, but of the body politic, mirroring some of the topics discussed in the fourth and final unit

on soil and belonging.

Opening Activity

Interview a friend/family member (gardner, wine lover, compost producer, etc.) about how they evaluate a good soil.

- What senses and means do they use to understand their soil?

- Where do judgments of soil come from? Or have they developed over time?

- If they don’t think they know the difference between good or bad soil, what information do they feel they lack to make that judgment?

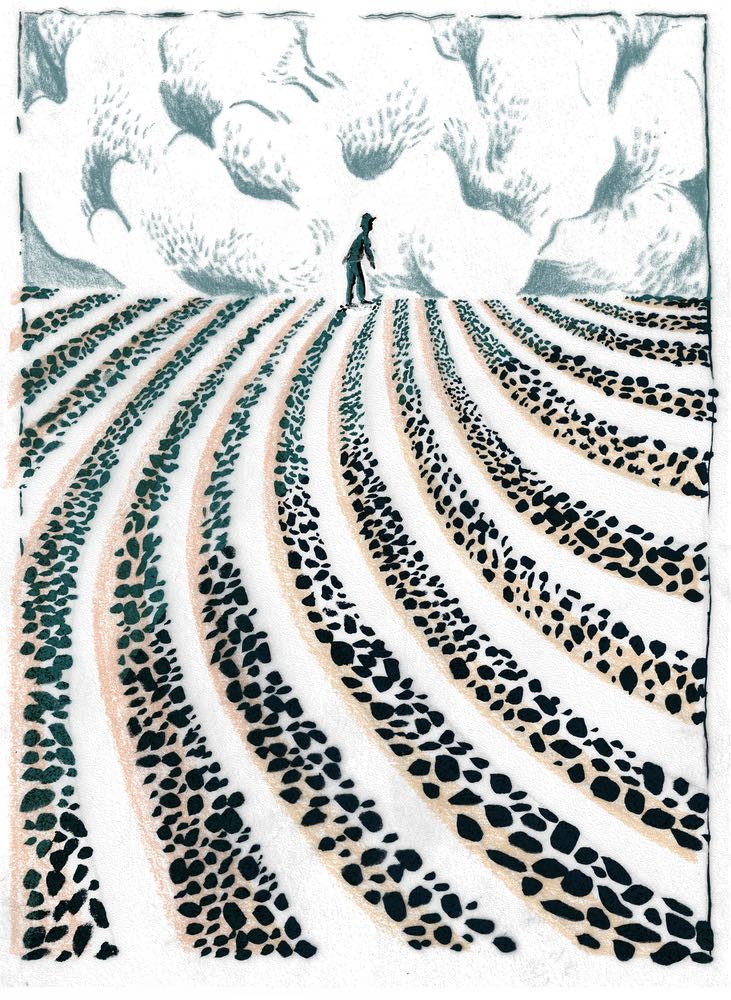

Activity: Experiencing the Dust Bowl, USA

The Dust Bowl was a series of dust storms, which destroyed farmlands in the Great Plains throughout the 1930s.

It is often considered the worst man-made ecological disaster in American history.

Read the excerpt from the letter of

Caroline A. Henderson, a farmer in Oklahoma,

to her friend in Maryland during the dust bowl, from 30 June 1935. Consider the following questions:

- How did Henderson understand the state of her soil?

- How did these environmental circumstances affect people’s lives, well-being, and choices?

- Does Henderson seem to wrestle with what caused these problems?

Activity 2: Soil Erosion, Soil Conservation, and Settler Colonialism

Soil conservationists of the 1930s and 1940s were deeply concerned with the problem of soil erosion, particularly

in colonial contexts. Much of their research was dedicated to historicizing global processes of desertification

during periods in which European powers were attempting to strengthen their hold onto arid and semi-arid territories.

Read the following excerpts from soil conservationists and the suggested readings below. Consider the following questions:

- How did soil experts understand the state of the soil?

- How did soil erosion relate to people’s lives, behavior, and choices?

- Who is considered responsible for the state of the soil, and what are the solutions to environmental problems?

- What sort of relationship between states and citizens (or colonial subjects) emerge around soil interventions?

1. G. V. Jacks and R. O. Whyte, The Rape of the Earth: A World Survey of Soil Erosion

(London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 1939), p. 26:

“Erosion is a modern symptom of maladjustment between human society and its environment. It is a warning that Nature is

in full revolt against the sudden incursion of an exotic civilization into her ordered domains. Men are

permitted to dominate Nature on precisely the same condition as trees and plants, namely on conditions that they

improve the soil and leave it a little better for their posterity than they found it.”

2. G. N. Sale, the Conservator of Forests of the British Government in Palestine, “Afforestation and Soil Conservation,”

lecture at the Palestine Economic Society, 28 December 1942, Israel State Archives/M-3/4188, 3-10:

“In our conservation work we have to ally ourselves with nature…nature herself is anxious to avoid such phenomenon,

and we can count on her assistance in our effort…we must not only prevent further damage to land still capable

of production, but we must take steps to repair the ravages of past neglect, and to restore the fertility

of land which has been ruined by erosion.”

Readings / Other Media

Activity 3: Seeing Contaminated Soil - Mining Waste, South-Africa

South-Africa’s long-lasting gold and uranium mining industries left a wide-scale disastrous mark on the soil and on people’s bodies.

- How is the contaminated soil experienced and evaluated?

- How is unhealthy soil related to human life trajectories?

- Who is considered responsible for the state of the soil and for mine workers’ health?

Lesson Plan

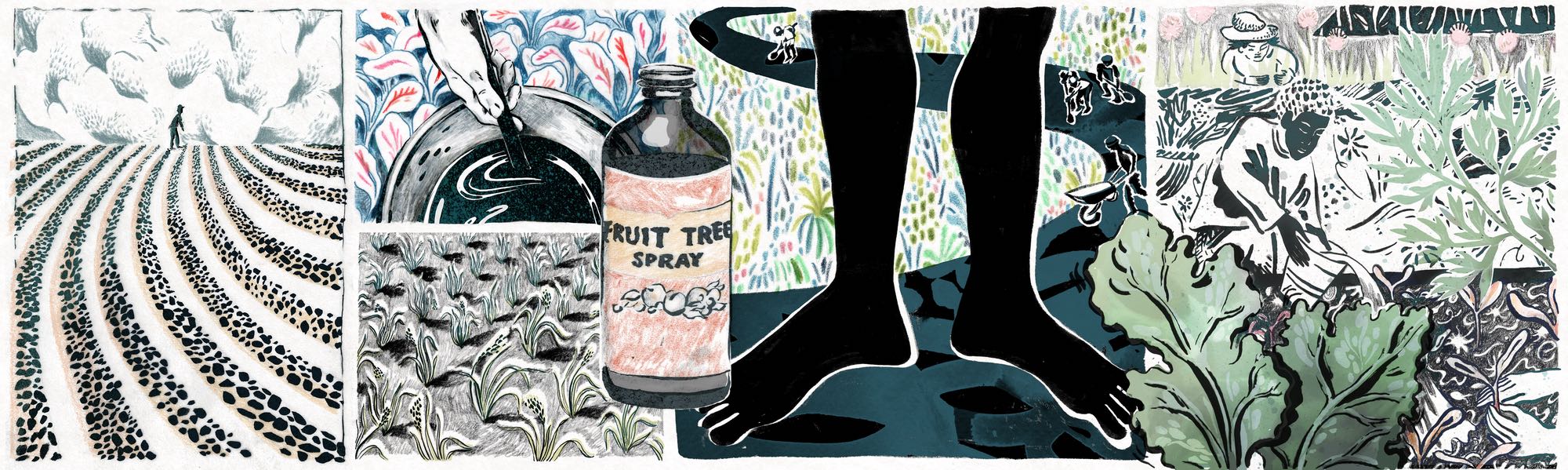

“In response to an agrarian crisis, small-scale farmers in South India are experimenting with the application of

agricultural ferments to their degraded soils” (Munster, 2021)

Think of any plant of your choice and find out what type of soil it grows in. Research information about

how it grows best and determine how you would take care of the plant and the surrounding soil.

Readings / other media

Read also The Government of Beans (2020) by Kregg Hetherington to consider how the imposition of capitalist

agricultural systems (monocrops) particularly since the “Green Revolution” have equated soil care with pesticide

use and fertilizer inputs. These have,paradoxically, often destroyed soil health as well as imperiled human

health and then sought solutions to the problems they have created rather than avoided the problems

in the first place:

Further reading:

Assignment 2

Browse through this collection of pesticide containers

and take notes on the following for discussion:

- What are some of the design and language choices used for marketing pesticides?

- Take note of dates: are there differences across time in how pesticides have been labeled and marketed?

- Who are the companies making these products?

- What else do you notice that surprises or intrigues you?

In addition, read “Chapter 11: Beyond the Dreams of the Borgias” in Carson, Rachel. Silent Spring.

(Boston; Cambridge, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1962). There are many places to find this online but

here’s one.

Lesson Plan: Soil, labor, and hookworm

Watch

- If we understand each video as a public health message shown to a population vulnerable to hookworm, how do they address each of these audiences?

- How does each video explain or otherwise show the cause of hookworm infection?

- If you were to critically respond to these videos, what is left out of the story here?

Read:

Scientists in the late 19th century had seen the hookworm under a microscope and understood its lifecycle passing from

soil to humans. As you can see from the Rockefeller archive and Norman Stoll, by the early 20th century, the hookworm

was seen as a major obstacle to development and progress at the same time that we can see that it is precisely the

spaces of capitalist agricultural expansion (such as tea plantations) where hookworm most quickly reaches

epidemic levels. Indeed, many people have and continue to suffer from the effects of hookworm infections.

- How does hookworm and soil help us put labor and health in the same analytical frame?

- Outside of a developmentalist framework, how do other cultures understand and live with worms?

- How might western biomedicine also be coming around to hookworm as an essential companion species for humans? And does this challenge the normative assessment of soil as dirty and even dangerous to our health?

Assignment

Find and watch some videos about black farmers in the US. How do they situate themselves and their practice of gardening

or farming? How does history figure in their relationship with the land? Do they articulate a connection between land

and health? How do they articulate the benefits of farming beyond a food harvest?

Here are some videos to start you off:

And a supplemental reading:

Or, to listen:

Reading and Discussion

Finally, soil is also a place where the violence of the past can linger on. Here are a few examples where artists and

communities are working with soil as a medium for healing from racial violence and dispossession. Why do you think soil

has emerged as such a popular medium for such work.

4. Soil as Belonging