Let’s follow Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s four moments through the botanical garden to examine the silences that may or may not be produced.

Step 1

Trouillot’s first moment is the moment a plant is collected. In this moment, the plant is pulled out of

the ground, meticulously disentangled from the soil, and made into a "type." Before the plant was pulled

from the ground it was just another plant in a world full of plants, but in the moment it is "collected"

it begins to stand in for the species in general. It is no longer specific to that piece of ground, to

that soil, or to its relationship with sun and shade in the place it grew. It is now a specimen. Let's

examine this moment of fact creation in the Missouri Botanical Garden archive.

Go to the Missouri Botanical Garden archival database:

https://livingcollections.org/home

Find a plant in the Missouri Botanic Garden (any plant) that you would like to explore. For example,

try searching: "Fraxinus americana."

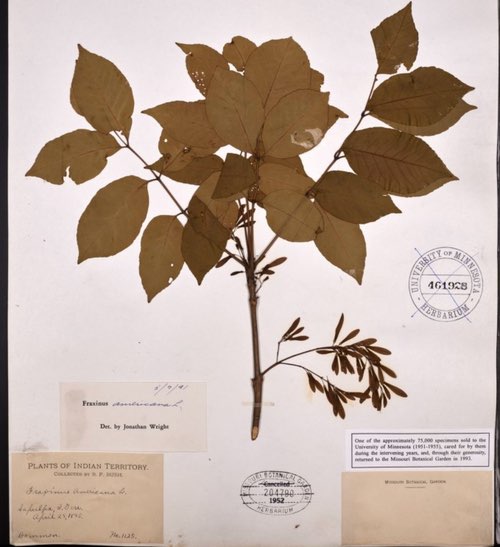

To find Trouillot’s 1st moment for this plant, go to one of the plant's herbarium sheets and look at it

closely. Who collected this plant? What was their name? Where did they collect it? Next, explore the links

associated with the plant. How many different ways has this plant (and plant species) been entered into

this database? As you explore the archive, you are now exploring Trouillot’s second moment: the moment

where the collected plant becomes part of a larger archive.

Step 2

Trouillot’s third moment is when we start to do things with the archive. This is when narratives are

constructed through the ability to retrieve information that the archive has made available to our thinking.

Directly next to the species name (maybe Fraxinus americana) of your plant in the Living Collections

Management System there will be a small Missouri Botanical Garden Logo. Click on this small logo.

This will take you to Tropicos, the MOBOT taxonomic database. What can you learn about the plant here?

Does the plant have an "author"? Who is this person? What other plants did they identify?

In the case of Fraxinus americana, the author is Linneaus himself, meaning that Linnaeus was the first

one to name this species. You'll also find citation information for the text in which the species first

appeared in writing. In this case, Tropicos tells us that Fraxinus americana was first identified by

Linneaus in the book Species Plantarum (1753). Next to this citation you'll see some more small logos...

one of them has the letters "BHL." Click on this link, which will take you to the Biodiversity Heritage

Library site: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org

Here, you will see a digital scan of the physical book from 1753 where Fraxinus americana first appeared.

Step 3

Trouillot’s final step is the making of history. This is where many narratives are considered and analyzed

in order to construct an account of the past. In this case, the plant was collected in 1941 by Jonathan

Wright as part of a collection he called "Plants of Indian Territory." Could we think of this plant's

history as exclusively taxonomic, or might think of the legacy of settler colonialism as an important

dimension of this plant's "territory?"

In the final step, you will research and write your own history of this plant. Consider what aspects of

this plant's history may have been left out of its presentation in the herbarium—for instance, more

about the person who collected it and the circumstances under which they did so; or alternative contexts

in which that plant may have gained meaning (e.g. within Indigenous knowledge systems). Drawing on this

research, write a blurb for this plant that “includes the soil”—that is, situates it within a political,

historical, ecological, and social context.